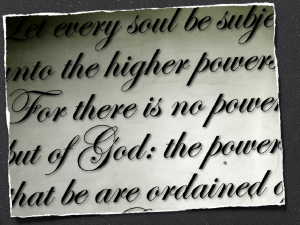

Let every soul be subject unto the higher powers. For there is no power but of God: the powers that be are ordained of God.---Epistle to the Romans, 13:1

America could hardly be a "Christian nation" founded upon such an unBiblical act!

However, in this 1818 letter looking back on the Revolution, John Adams describes the colonists' theological justification for the war: They didn't fire King George, he quit.

February 13, 1818The American Revolution was not a common event. Its effects and consequences have already been awful over a great part of the globe. And when and where are they to cease?

But what do we mean by the American Revolution? Do we mean the American War? The Revolution was effected before the War commenced. The Revolution was in the minds and hearts of the people, a change in their religious sentiments of their duties and obligations.

While the king, and all in authority under him, were believed to govern in justice and mercy according to the laws and constitution derived to them from the God of nature, and transmitted to them by their ancestors, they thought themselves bound to pray for the king and queen and all the royal family, and all in authority under them, as ministers ordained of God for their good. But when they saw those powers renouncing all the principles of authority, and bent upon the destruction of all the securities of their lives, liberties, and properties, they thought it their duty to pray for the Continental Congress and all the thirteen state congresses, etc.

There might be, and there were, others who thought less about religion and conscience, but had certain habitual sentiments of allegiance and loyalty derived from their education; but believing allegiance and protection to be reciprocal, when protection was withdrawn, they thought allegiance was dissolved.Indeed the Declaration of Independence reads:

2) "He [King George III] has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us."And so the colonists--in harmony with Romans 13--transferred their allegiance to the duly constituted authorities, those of their state governments, and of the Continental Congress. Parliament was not their constituted government—the colonists did not and could not vote for or against them.

6 comments:

This probably has been covered already at AC, but the rebellion had been going on for several years before the DofI. The Parliament laid the blame squarely on the colonists for starting it all.

But what about all those events that preceded the Prohibitory Act? Were they not all in violation of Romans 13 and other scriptures?

And it was those events that convinced Parliament that the colonists started it all . . .

WHEREAS many persons in the colonies of New Hampshire, Massachuset's Bay, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, the three lower counties on Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia, have set themselves in open rebellion and defiance to the just and legal authority of the king and parliament of Great Britain, to which they ever have been, and of right ought to be, subject; and have assembled together an armed force, engaged his Majesty's troops, and attacked his forts, have usurped the powers of government, and prohibited all trade and commerce with this kingdom, and the other parts of his Majesty's dominions: for the more speedily and effectually suppressing such wicked and daring designs, and for preventing any aid, supply, or assistance being sent thither during the continuance of the said rebellious and treasonable commotions, be it therefore declared and enacted . . .

etc. etc. etc.

And do these acts themselves violate Rom 13 as well as other scriptures?

Heh heh. Alexander Hamilton covered that one in The Farmer Refuted. The colonies have their charters from the crown, not Parliament. They owe no obedience to Parliament or to their oppressive laws.

If we examine the pretensions of Parliament by this criterion, which is evidently a good one, we shall presently detect their injustice. First, they are subversive of our natural liberty, because an authority is assumed over us which we by no means assent to...For such security can never exist while we have no part in making the laws that are to bind us, and while it may be the interest of our uncontrolled legislators to oppress us as much as possible.

...

The idea of colony does not involve the idea of slavery. There is a wide difference between the dependence of a free people and the submission of slaves. The former I allow, the latter I reject with disdain. Nor does the notion of a colony imply any subordination to our fellow-subjects in the parent state while there is one common sovereign established. The dependence of the colonies on Great Britain is an ambiguous and equivocal phrase. It may either mean dependence on the people of Great Britain or on the king. In the former sense, it is absurd and unaccountable; in the latter, it is just and rational. No person will affirm that a French colony is independent on the parent state, though it acknowledge the king of France as rightful sovereign. Nor can it with any greater propriety be said that an English colony is independent while it bears allegiance to the king of Great Britain.

But you deny that “we can be liege subjects to the king of Great Britain while we disavow the authority of Parliament.” You endeavor to prove it thus:1 “The king of Great Britain was placed on the throne by virtue of an Act of Parliament, and he is king of America by virtue of being king of Great Britain. He is therefore king of America by Act of Parliament; [67] and if we disclaim that authority of Parliament which made him our king, we, in fact, reject him from being our king, for we disclaim that authority by which he is king at all.”

Admitting that the king of Great Britain was enthroned by virtue of an Act of Parliament, and that he is king of America because he is king of Great Britain, yet the Act of Parliament is not the efficient cause of his being the king of America. It is only the occasion of it. He is king of America by virtue of a compact between us and the kings of Great Britain. These colonies were planted and settled by the grants, and under the protection, of English kings, who entered into covenants with us, for themselves, their heirs, and successors; and it is from these covenants that the duty of protection on their part, and the duty of allegiance on ours, arise.

So that to disclaim the authority of a British Parliament over us does by no means imply the dereliction of our allegiance to British monarchs. Our compact takes no cognizance of the manner of their accession to the throne. It is sufficient for us that they are kings of England.

The most valid reasons can be assigned for our allegiance to the king of Great Britain, but not one of the least force or plausibility for our subjection to parliamentary decrees.

We hold our lands in America by virtue of charters from British monarchs, and are under no obligations to the Lords or Commons for them. Our title is similar, and equal, to that by which they possess their lands; and the king is the legal fountain of both. [68] This is one grand source of our obligation to allegiance.

_________________

The Declaration echoes this rejection of the authority of Parliament.

"Nor have We been wanting in attentions to our Brittish brethren. We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here. "

The problem of the authority claimed by Parliament, Crown, Boards of Trade, and colonial legislatures speaks to the crux of the dispute with Britain-- a constitutional conflict (covered by one of my favorite historians . . .

http://www.amazon.com/Constitutional-Origins-American-Revolution-Histories/dp/0521132304/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1425626816&sr=1-1&keywords=jack+greene

And your quotes by Hamilton reveal what the colonists sought--something like the later British commonwealth of nations.

But once we get to the DofI, do not the indictments of George based upon him becoming a tyrant still contradict Rom13. with does not explicitly offer any allowance for disobedience based upon tyranny, liberty, consent of the governed?

The British had been through this once already. In the Glorious Revolution of 1688, King James II "abdicated," yielding the crown to William and Mary. Problem solved.

It looks like Rom 13 did not inhibit Englishmen either.

Aquinas had been flirting with regicide as early as the 1200s, and the "Policratus" before that. [John of Salisbury was the bishop who "avenged" Henry's murder of Becket. Interesting provenance.]

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tyrannicide

Post a Comment